By Dr. Terry Stoops

Every February, the Information Analysis section of the Division of School Business at the NC Department of Public Instruction (DPI) publishes “Highlights of the North Carolina Public School Budget.” This year, the publication of the report was delayed by three months. I can’t imagine why.

The report focuses on state and federal funding. Test scores, graduation rates, and other outcome measures are not included. Further, it has limited information on the use of local funding or school-based expenditures. Despite these limitations, Highlights remains a useful resource for examining trends in education spending, teacher compensation, and capital outlay.

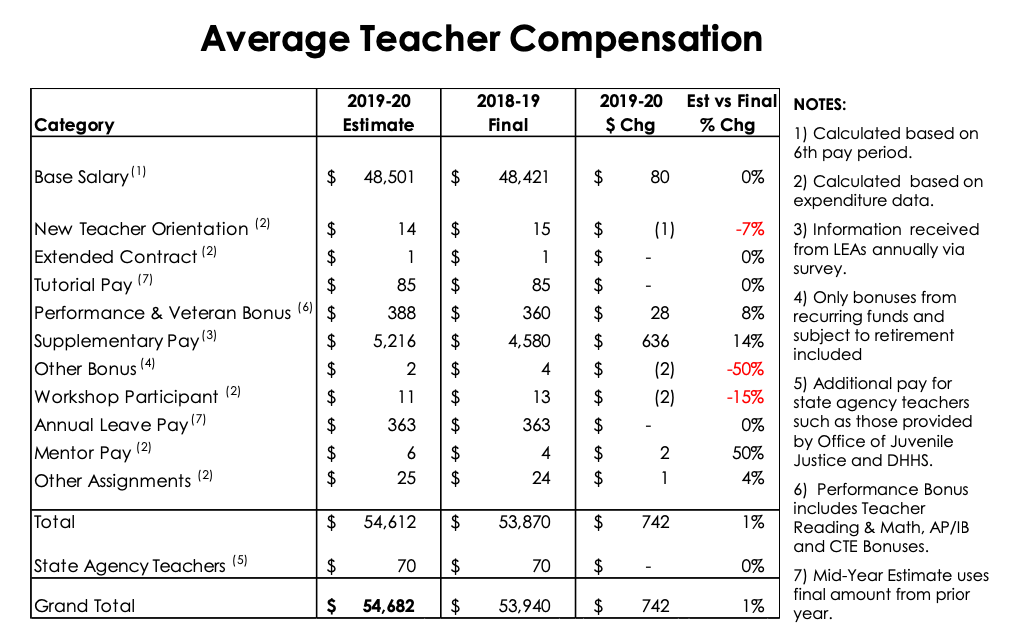

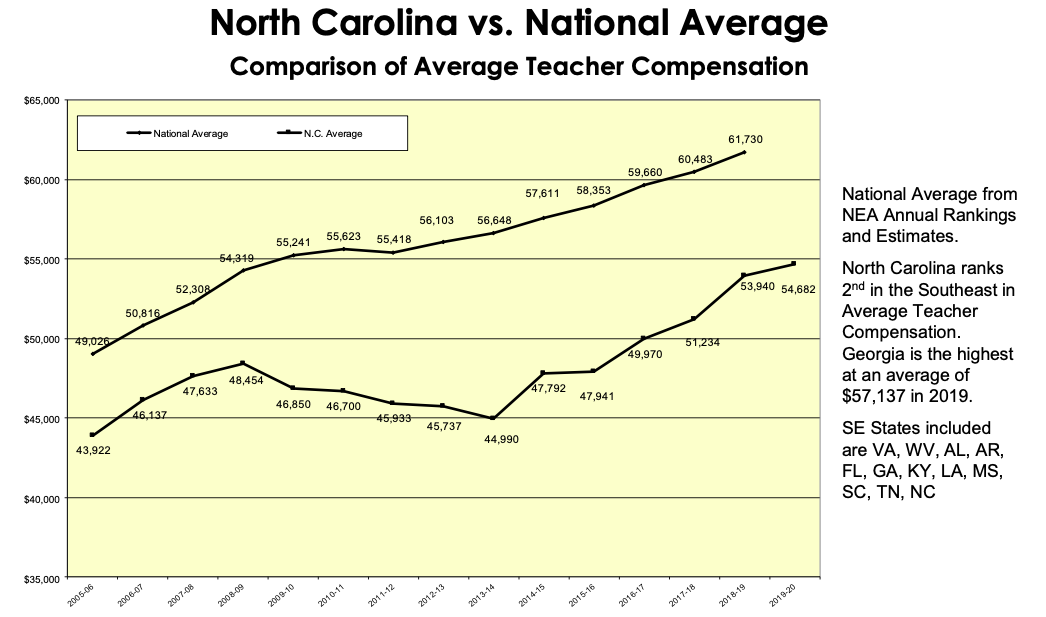

According to DPI budget analysts, North Carolina’s average teacher salary reached $54,682 this year. The 2019-20 average was an increase of $742 or 1.4% compared to the previous school year. DPI declares that North Carolina’s average teacher compensation ranks second only to Georgia in the Southeast. Last year, North Carolina ranked fourth in the region.

In recent years, North Carolina teachers have enjoyed sizable pay increases thanks to state legislators and county commissioners. The statewide average salary rose from $44,990 in 2014 to $54,682 in 2020, a 21.5% surge featuring a 5.3% increase in the average between 2018 and 2019. This led to a steady climb in the popular National Education Association (NEA) teacher salary rankings. Last year, North Carolina’s $53,975 average teacher salary ranked29th in the nation. When adjusted for cost of living, the state reached the top 20. The NEA has not released teacher pay rankings and estimates for the current school year.

Why was this year’s increase relatively small compared to previous school years?

Gov. Cooper’s veto of the Republican budget (and Senate Republicans’ inability to muster enough Democratic support for an override) thwarted plans to boost teacher salaries further. In November, Cooper signed Session Law 2019-247, which was legislation that granted experienced-based or “step” salary increases for teachers, instructional support personnel, and assistant principals. The step increases helped some but not all teachers.

North Carolina school districts must use common experience- and credential-based salary schedules that are included in each state budget. They are adjusted if lawmakers award pay increases. The approved salary schedules for the current year granted $1,000 raises to teachers in their first 15 years in the profession. No other teachers, except those moving into their 25th year, received an increase.

State schedules establish minimum salaries. Teachers also receive performance bonuses, annual leave pay, and, most importantly, local salary supplements. Local supplements are additional payments provided to teachers by their school district using local tax dollars. This school year, 109 of the state’s 115 school districts provided local supplements to their teachers. According to the Highlights report, districts provided an average $5,216 supplement, a $636 or 14% increase over the year before. This significantly higher local salary supplement accounted for nearly all of the year-over-year increase in the state average.

Does any of this really matter?

Five years ago, I explained that average teacher pay statistics are misleading. For example, changes in the composition of the workforce, such as hiring greenhorn teachers to replace seasoned educators, may depress the state average. In a 2016 WRAL article, a DPI official concurred with that assessment.

Alexis Schauss, director of school business for the state Department of Public Instruction, says average teacher pay does not take into account the experience level of teachers in different states. When North Carolina’s average teacher pay went down in previous years, it wasn’t because teachers were paid less. The population just became less experienced.

Public school advocacy groups contend that statewide averages are misleading because they obscure variations in pay within and across school districts. Curiously, most didn’t express their objections publicly until Republicans began pouring taxpayer dollars into teacher salary raises.

Average salaries reveal nothing about the relative quality or productivity of the teacher workforce because, as mentioned above, North Carolina does not pay teachers based on quality or productivity. Additionally, pension and health insurance are significant expenses. According to the Highlights report, state lawmakers allotted $2.4 billion for employee benefits in 2019. As the cost of providing benefits increase, lawmakers have less capacity to fund pay raises.